People have been fascinated with the insane,

and, consequently, with their art, really since the dawn

of psychology as a legitimate field of study. In the late

19th century, psychology distinguished itself from physiology

and other sciences, as Freud was making breakthroughs

in the inner-workings of the mind, particularly with the

development of the theory of the conscious and subconscious

as distinct pieces of the psyche. Coinciding with this were

the changes occurring in the evolution of modern art. Artists

were ever more leaving behind the academia-style art and

were beginning to favor a less realistic approach, (as they

had for at least a century by this time) and moving with

and even from what was already radical, impressionism, and

eventually delved into surrealism.

Their new taste in art stressed the free flow of spontaneous

thoughts, essentially making art that wasn’t planned.

Abstraction was more common since there was no reason to

paint accurate depictions as the photographs were doing

just fine with that. Also, with this abstraction, came an

interest in art that was unpolluted from the constraints

and ideals of society. A free, unique independent art came

about, that looked to the children and “primitives”

for direction, instead of the schools. With these inspirations

came the fascination with the insane, who were also considered

more natural and free in their art, like the children and

“primitives.” These people, who were shielded

from corruption by society as they were imprisoned in their

own minds, were unable to correspond with society in a manner

that the sane do. In addition, their being locked up in

mental “hospitals” in large numbers at this time

contributed to their physical isolation. Thus, definitely

not producing art for money’s sake, nor for fame, nor

for any reason previously known to artists, the insane art

was purer than ever. The insane “create solely to

externalize their internal visions and to satisfy their

own internal needs (Delamonthe 1301).” The insane

aren’t even aware they are making art many times. Beginning

in the 19th century, insane art was not only observed, it

was promoted. While Freudians swarmed them to learn about

the abnormal mind, artists watched as the therapists encouraged

art as a way to relinquish stressors and also as a materialistic

insight into the strange workings of their disturbed minds,

in hopes of finding a cure.

Despite Plato

seeing a connection between creativity and insanity, and

this same belief affirmed by the Renaissance artists, it

lay dormant for a couple hundred years before resurfacing

during the 19th century. By today, people now realize that

the line between genius and insane can be so incredibly

fine. Who is to say that Vincent Van Gogh was not

an “outsider” (as these social recluses are now

called by the art community)? Or what about the great prose

of Edgar Allan Poe? We now think he had a fight with

insanity too, specifically, with bipolar disorder, known

to strike many artists in all mediums: painters, writers,

musicians, etc. In this sense we might be able to posit

that insanity increases creativity by nature, that it aids

in the production of works of art that otherwise sane individuals

have to strain and toil long hours studying how to replicate

artificially, as we might see the surrealists doing. We

then are led to wonder though, is it the art that brings

on the insanity or are the insane drawn to art? It was said

by the late 19th century Italian psychiatrist Cesare

Lombroso, that all paintings by “lunatics”

exhibited the same basic characteristics. These included:

distortion, repetition, minute detail, arabesques, obscenity,

and rampant symbolism (Porter 49). The connection

psychiatrists were making at this time between artists and

insane art was so solid, that they later believed all art

that exhibited these qualities had to be done only by the

insane. According to Theophilus

Hyslop, the cubists were suffering from neurological

disorders that somehow were connected to their eyes.

|

|

But the most important characteristic of insane

art is its creativity. It seems if we were to measure art

simply by terms of creativity, we’d find that the top

quality pieces would be that of the insane. However, clearly

this is not the only aspect to art. Nevertheless, the impact

the insane had and have on art is remarkable.

The surrealists attempted to do, in a sense,

was copy this free conscious, insane art by using their dreams

as blueprints for their pieces. While not too abstract and

chock full of symbols to lose all obvious coherence (and thus

the comprehension of the onlooker), the surrealists painted

what was bizarre and strange while keeping it in a worldly

context we are all familiar with. It was in their unique,

or rather simply otherworldly juxtaposition of familiar objects

and places that made the art surreal. Dali’s famous melting

clocks are a perfect example. In addition, Paul Klee, Max

Ernst, Jean

Dubuffet, and Georg

Baselitz all claimed to be heavily influenced by outsider

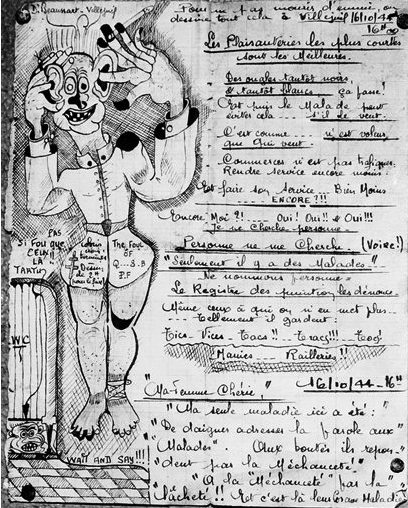

art. However, insane artist Antonin

Artaud once wrote in response to what he might’ve

seen as the manipulation and bastardization of his art and

other insane artists’ by the liberal minded surrealists.

A strikingly sobering line, he said, “What divides

me from the Surrealists is that they love life as much as

I despise it (Kuspit 83).”

As for the madmen, and their more authentic surrealist paintings,

no one seems to be held in such esteem (if that is the proper

word for the appreciation of the insane) than the Swiss

psychotic Adolf

Wolfi. Born in 1864, he was put into a mental hospital

in his 30’s and died their about 30 years after his arrival.

A convicted child molester, he seemed to have been obsessed

with little girls since he was prevented from marrying a teenage

sweetheart of his at the age of 18 because her parents deemed

him too low-class. The obsessive detail of his 3000 illustrations

is uncanny. Also, his choice of medium is as varied and wild

as the characters he drew and painted. His “Waldorf

Astoria Hotel” of 1905, is done in pencil on four

sheets of newspaper about 10 feet long. In it, he has 4 hotels

depicted as lavish palaces, covered to the point of explosion

with detailed, ornately decorated facades. Amazingly, the

painting has been compared to cubism, another genre in the

modern art scene, in that the “tones subtly advance

and recede, knitting together a shallow visual space…(Schjeldahl)”

It has been said of “outsider art” that it is too

repetitive, which is naturally a solid complaint since most

of the insane are obsessive in nature. Obsession is an adjective

we commonly use to describe those we call mad. Even today

it riddles psychiatric terminology with all the various “diseases

of the mind” which have been only recently diagnosed

and given new appellations, like ADD and OCB…the latter

even stands for Obsessive Compulsive Behavior. However,

it is within this new framework of psychiatric treatment,

that we finally see the decline in the obsession or fascination

with outsider art, both within the artist community and in

the art-loving community, the patrons.

In the late 20th century, as medicine became ever more “effective”

in “treating” these “disorders,” the insane

artists found their minds ever dulled and quieted by the new-age

drugs. They could no longer produce such fantastic works because

their creativity, which was so prized by the modern artists,

was dissolved. Even too was the original fascination of the

psychologists, who now are more of medically oriented brain

doctors, resorting to chemicals for their treatments as oppose

to the old forms of therapy and counseling, which included

art.

The insane were, in the beginning of the 20th century, sadly

locked away in asylums and treated with electric shocks and

other horrible detrimental “treatments.” Ironically

though, they were also given loads of pencils, paints and

other materials to occupy them, in hopes that this would keep

them from violent behavior. With all the time on their hands,

being locked up 24-7, away from reality, the outside world,

they found refuge in their art, where a newly created world

of their own devices, had found a place to manifest itself.

With this society of the insane dispersed and obliterated

by drugs and more “humane” treatments, the art of

the insane may have ultimately found its demise, at the hand

of those who had once appreciated and cultivated it.

Works Cited

Delamothe, Tony. "Mad About the Art."

British Medical Journal, Nov 21,

1992 v305 , n6864 p1301(1)

Kuspit, Donald. "Antonin Artaud: works

on paper." Artforum International,

Jan 1997 , v35 n5 p80(2)

Porter, Roy. "But is it art? The Difference

between a Paul Klee and a painting by a psychiatric patient

is all in all the mind of the beholder." New Statesman,

Dec 6, 1996 v125 n4313 p46(3)

Schjeldahl, Peter. "The Far Side."

The New Yorker, May 5, 2003 v79 i10 p100

Back to 2004 Contents

- Next

|