| [NEWTON, Isaac]

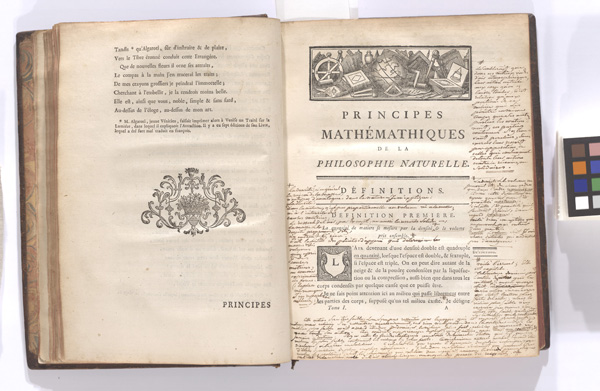

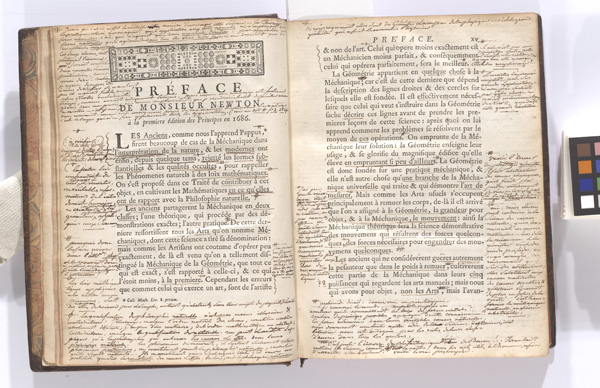

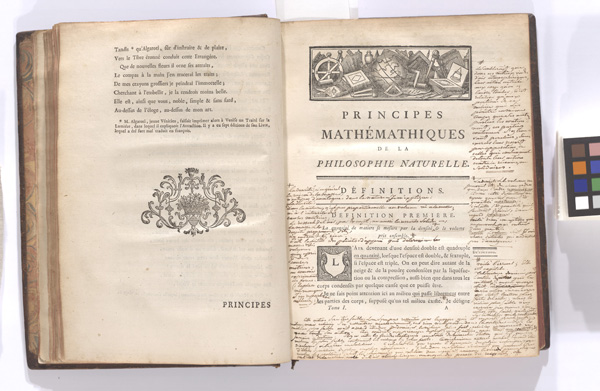

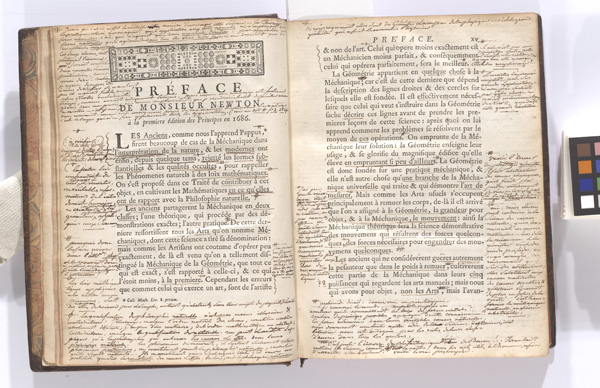

CHATELET, Marquise du Principes mathematiques de la philosophie naturelle Paris: Desaint & Saillant, 1759. First complete edition. Two volumes 4to, [iv],xxxix, [v], 437, [1]; [ii], 180, 297, [3] pp. 14 folding plates. Contemporary calf. Madame de Chatelet, under the guidance of Voltaire, made the first (and what is still the only) definitive translation of Newton's Principia into French. By this time the western world had largely accepted that Newton had formulated a mechanistic natural philosophy that correctly described gravitation and celestial mechanics, replacing the competing and largely qualitative Cartesian philosophy with a quantitative physics. It is widely supposed that Newtonian and Cartesian science predicted different characteristics of observable phenomena (such as the shape of the earth), and thus that the better science would be the one that made the correct prediction, but in fact the distinction was that Newtonian mechanics made quantifiable predictions while Cartesian mechanics did not. Thus the success of Newtonian physics derived from its practical utility. In essence, Cartesians were more concerned with causes while Newtonian science was more concerned with effects. Newton himself underscored this point in the General Scholium to the second edition of the Principia in his famous pronouncement hypothesis non fingo (I frame no hypotheses) about the mechanism or cause of gravitation. However, a rear guard of Cartesians (mainly French Jesuits) continued in a vain attempt to find physical phenomena that were not correctly described by Newtonian mechanics, while arguing vigorously with its philosophical foundations. This copy of Chatelet's translation was owned and annotated by one such person. The first fifty pages of the book, where Newton presents his fundamental axioms and laws, and his philosophical position, are almost completely covered, in the margins and between the lines, with a dense and highly animated counter-argument from the Cartesian standpoint. Although the annotator has not yet been identified, there is circumstantial evidence that it might have been Etienne Bertier, a Jesuit who was an active opponent of Newtonian physics. The annotations make reference to experiments reported in 1769 by Coultaud that claimed to demonstrate inconsistencies in the strength of the gravitational force between the base and the summit of a mountain in the alps. Bertier based part of his own book Les principes des physics on these experimental results. Bertier also made his own measurements with a balance and claimed to find discrepancies. The Coultaud measurements were later revealed to be a fraud and Bertier independently retracted his own experimental conclusions after reconsideration. That was arguably the last Cartesian gasp that could have been assigned even a shred of credibility. Heavily annotated books such as this one, echoing the voices of long dead readers and writers, provide a unique insight into the scholarly and scientific combat that shaped the modern world. |

|