|

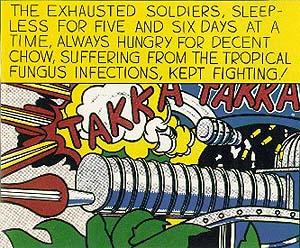

Roy Lichtenstein was born in New York in 1923. While growing up on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, he attended public school and then at twelve, he went to Franklin School, which did not offer any art classes. Despite this he taught himself how to draw, and at age fifteen he decided to be an artist rather than a scientist. His parents supported his decision and, after graduating high school in 1940, he attended the Arts Student League. He eventually transferred to the School of Fine Arts at Ohio State University where he became interested in "the difference between a mark that was art and one that wasnít" (Tomkins 15). In February of 1943, Lichtenstein was drafted in to the U.S. Army, in which he served from 1943-1946. After the war, he returned to Ohio State University, graduating with a BFA in 1946 and a Masters Degree in Fine Arts in 1949 (Alloway 9). During this time he also worked at OSU as an art professor, a position he held until 1951. His first solo exhibit was in 1951 in New York City at the Carlebach Gallery. At this time, his work consisted of semiabstract paintings that were derivative of Picasso and Klee. His subject matter, however, was primarily knights and medieval castles (Tomkins 16). |

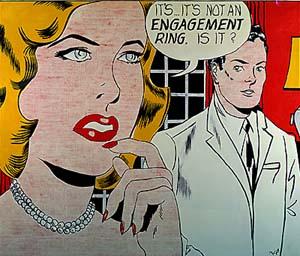

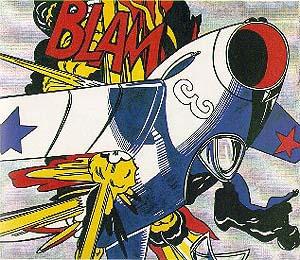

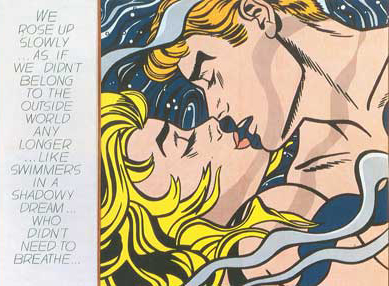

During the Fifties, he lived in Cleveland, creating art in the time he had between temporary jobs. At this time (1952-55), his art centered on the Far West and American history, which was then followed by an Abstract Expressionist phase (1957-60). This work was shown in a series of one-man art shows. In 1957, he obtained a teaching position at State College of NY at Oswego. It was around this time that images from comics began to be incorporated into his abstract compositions. Elements of his future style were beginning to emerge. Similarly, Lichtenstein painted a ten-dollar bill in a Cubist/Expressionist style in 1958. According to Lichtenstein, it was the first time he had the idea of "doing really simpleminded pictures that would look inept and kind of stupid, and the color would look at though it wasnít art" (Tompkins 17). However, he said, "to be commercial-art-looking in an unartistic way didnít really occur to me until 1961" (Tompkins 17). This was while he was teaching at Douglass College, Rutgers University in New Jersey. By 1962, he had an influential art dealer named Leo Castelli. Lichtenstein was now able to support himself as an artist, which caused him to resign from teaching in 1964. This independence allowed him to produce a prolific amount of work, and led to him becoming hugely successful. It was during this period that he began to produce pop art, focusing on commercial subject matter such as comic art and advertising. Due to his success in this area, two early retrospectives of his career were done by the Pasadena Art Museum in 1967 and by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, NY in 1969 (Alloway 15). |

|

|

Lichtensteinís Comic Pop Art |