Vodou

I know that the loa live in the earth, in the rivers, under the

sea, in the waters of the lake, in the sun when it rises or sets, in the

seasons, in the harvests, in the smile of the stars…How could they not live

eternally in the heart of men?

-Jacques-Stephen Alexis, The Tree

Musicians

Introduction

Vodou1 is a religion practiced in Haiti that

was brought over by the Aradas from Ouida on the West Coast of Africa during

the height of the slave trade and “although in the most restricted sense it

refers only to Arada rites, the word Vodou has over the years come to stand for

all African-derived religious practices in Haiti” (Fernandez-Omos and

Paravisini-Gerbert 102). The term

means “spirit,” “god,” “image,” or “sacred energy.” Vodou is rather miraculous in the plethora of Caribbean

religious traditions because despite frequent repression and persecution, many

of the traditions used by the first slaves imported to Haiti are still adhered

to by the practitioners today.

Though it is creolized with elements from Catholicism and other African

practices, it has adapted those practices to suit its need instead of adapting

Vodou to suit the needs of Catholicism.

Vodou is traditionally a religion of resistance to colonial power, and

its mischaracterization as a religion of “black magic” is directly related to

this fact and to the obvious point that writing Haiti as a nation full of

cannibals and zombies justifies the presence of colonial, civilizing forces from

the French to the United States.

As Joan Dayan suggests, “a mythologized Haiti of zombies, sorcery, and

witchdoctors helps to derail our attention from the real causes of poverty and

suffering: economic exploitation,

color prejudice, and political guile” (14). Despite poverty and colonization, however, practitioners of

Haitian vodou continue to maintain their communal practices and adhere to the

philosophy that the vodou gods share in their everyday experiences, though the

gods of Haiti are always being reborn and reconstructed. Vodou is ultimately a religion of

memory, it is “a story passed on through generations of Haitians who remember

the gods and ancestors left out of books, who bear witness to what standard

histories would never tell” (Dayan 23) and its varied stories are open to

multiple meanings to be interpreted through ceremony by its practitioners.

Beliefs and Practices

Practitioners

of vodou have retained the West African belief of a Supreme God called Le

Bon Dieu or Le Grande

Maitre who does not require

the worship of mankind because he is already predisposed to like man. Instead, worship is directed at loa2

who number in the hundreds, and who are the primary actants in the day-to-day

lives of human beings. Many loa are African in origin, but many also come

to be identified with Christian saints and many more were created or modified

to suit the needs of the displaced Africans living in the New World. Saints that were appropriated as loa were given personalities and attributes

that were not from Biblical sources or Catholic traditions. For example, St. John is supposedly

disposed to a desire for alcohol and the meat of black cattle and white sheep,

and though many vodunists attend the Catholic Church, their understanding of

the world is Vodou. The loa can be classified as best as possible by

their personality attributes and by the groups, nations, or tribes to which

they belong. Vodou has developed a

rich ceremonial and ritual aspect in which they honor, summon, and question the

loa.

Vodou

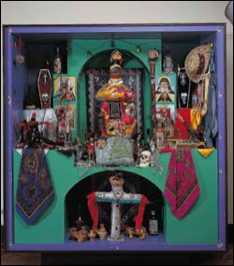

ceremonies take place in a community at the hounfort, the temple or vodou house. At these houses (and sometimes at

private homes), the objects displayed are a mixture of Catholic and African

paraphernalia such as thunder stones, flowers, and food especially liked by

that particular god. As Joan Dayan

asserts, “Each god has his or her own alter, which contains a mélange of

objects, flowers, plates of food and drink, cruches and govis—the earthen jars or bottles belonging

to the spirits of the dead—and the pots-de-tźte, which contain the hairs or nail parings of

the initiates there kept safe from harm” (17). The objects place upon the loa’s alter capture the personality and attributes

of the loa. The loa are perceived as functioning in the everyday

lives of the men and women who practice vodou, and the objects they desire are

both the treasures and the hurts of Haiti and the Haitian people, “what appears

as randomness is actually a tough commitment to the facts of this world.

The gods relate to and are activated by things that do not conform to

cravings for purity or longings for transcendence” (Dayan 18). Due to the involved nature of the

loa, the ceremonies that

take place in the hounfort involve

a summoning of particular loa

by marking the vévé (visual

symbol) of that particular god on the ground. The first deity to be invoked is Legba because he is the god

who ‘removes the barriers’ between the living world and the spirit world. He is the gatekeeper of the other

world, and thus his permission must be asked before any of the other gods can

be spoken to. Since he is the

protector of the barrier between the spirit world and the human world, he is

also the protector of the home.

Erzulie is another loa who

is frequently summoned and she is the goddess of love and luxury, portrayed

artistically as a light-skinned Creole who is the personification of beauty and

grace. Her vévé is filled with

sensuality, luxury, and unrequited love.

Loa are summoned

for their function in the human world, and may be called upon to help with a

love problem, with a harvest, a political situation, or any number of human

activities.

After

being summoned, the loa speaks

through a “horse” or a body that he or she possesses in order to communicate

with the adherents, and the serviteur (the one who is possessed) goes “through a set of violent

contortions” (Bisnauth 168).

Behavior during possession depends on the personality of the loa in question, and they “allow the loa to communicate in a concrete and

substantial way with their congregation, allowing them to ask pressing

questions and to receive guidance and advice” (Fernandez-Omos and

Paravisini-Gerbert 123).

Possession, contrary to popular belief, is not a matter of dominion,

since the serviteur and

the loa mutually rely on

one another. The loa needs a body in order to communicate, and

the possessed “gives herself up to become an instrument in a social and

collective drama” (Dayan 19). Once

a god has been summoned and a possession has occurred, it is interpreted that

the loa will meet the

request of those gathered.

Along

with the loa, the

universe is thought to be peopled by dead ancestors and by the dead in

general. This is why the most

important vodou ceremonies surround the release of the petit bon ange or the shadow of a person from their

corporeal body, so that they are not trapped in the world of the living. The dead of vodou practitioners fall

into several categories:

- Zombie errants: spirits of people who died unnaturally.

- Diablesse: spirits of women who died as virgins.

- Lutins: ghosts of children who died before they were

initiated.

- Bakas: zombies that have been converted into animals, usually

dogs, by sorcerers.

- Spectres and Fantomes: inhabitants of the other world who appear before the

living stripped of their bodies.

- Revenants: dead who feel they have been neglected and return to

persecute their relatives.

- Marassa-jumeaux: spirits of dead twins, held in special reverence by

practitioners of vodou.

The popular notion

of a zombie is that of a dead person brought back to life by black magic and

controlled by another person. Wade

Davis, in his groundbreaking ethnobiological study of Haitian vodou, The

Serpent and the Rainbow,

demystified zombification by providing the formula for the drug that, in some

cases, can make a person seem dead and once given an antidote, is controlled by

the person who administered the poison.

According to Davis, this practice was a tool of Bizango, a secret society, to sanction one of their

members who violated its codes.

Despite this demystification, “Zombification continues to be perceived

as a magical process by which the sorcerer seizes the victim’s ti bon ange—the component of the soul where

personality, character, and volition reside—leaving behind an empty

vessel subject to the commands of the bokor” (Fernandez-Omos and

Paravisini-Gerbert 129). Many

scholars and authors view zombification as a metaphor for colonialism, and

zombies continue to be one of the most feared beings in Haitian vodou.

Politics of the Movement

Vodou

has traditionally been a religion of resistance to colonial power in

Haiti. For example, one group of

3500 hundred slaves fled the plantations into the hills, and specific vodou

rites were developed among them.

They became known as the Petro practitioners, and they “were born in

protest against slavery and…the theme of revolt, ‘Vive la liberté,’ was

dominant in Petro ceremonies” (Bisnauth 170). Vodou inspired slave revolts between 1750 and 1790,

culminating in the August 1971 Turpin Plantation revolt led by Boukman that came just

before the St. Domingue revolution.

Boukman was “undoubtedly a worshipper of African divinities” and “it was

a Petro ceremony which he conducted on the night of August 14, 1791, that he

inspired the slaves to revolt” (Bisnauth 171). Though vodou was periodically suppressed after Independence,

it has nonetheless survived and still continues to be a major part of the

political and social sphere.

As

Joan Dayan asserts, “whether President Eli Lescot’s support of the church and

its ‘antisuperstition’ campaign in 1941 to clear peasant land for United States

rubber production or ‘Papa Doc’ Duvalier’s cynical deformation of what he

called a uniquely

Haitian tradition,” vodou continues to serve a political purpose (14). The use of vodou was negative when

appropriated by Papa Doc Duvalier and his secret police. While he was ruler of Haiti, he would

dress as Baron Samedi who is famous for sending thousands to their grave, as

did Papa Doc. The violence of the

secret sects of vodou and of Papa Doc’s police merged with the criminal loa, and random reports of terror by the loa

were merged with reports of

terrorism by Papa Doc. Vodou, then,

became more and more associated with darkness. Further related to the recent “darkness” of vodou, the

economic situation of Haiti forces peasants to be displaced from the ancestral

land where the loa reside,

forcing them into cities where they are too poor to serve the loa, resulting in the proliferation of “bad

magic.” The petit bon ange, which is inseparable from what constitutes

our personality or thoughts, is what the loa depend upon for possession, and “without the

loa, the petit bon

ange in turn loses its

necessary anchor: the petit bon

ange will be free-floating,

attaching itself to anything, or in its dislocation be stolen by a sorcerer and

turned into a zombie” (Dayan 31).

It is from the constant displacement and exploitation of the peasant

class that the “bad magic” of zombification is born. Zombies are directly related to the neocolonial interests of

places like the United States, who continue to exploit Haiti for its resources

and for its labor.

Zombies,

therefore, are part of the collective memory and present reality of

colonialism, since “the most horrible projections of the victimized are no

worse than the macabre facts of their daily life” (Dayan 32). Dayan explains that zombies are “born

out of the experience of slavery and the sea passage from Africa to the New

World, the zombi tells the story of colonization: the reduction of human being into thing for the ends of

capital” (33). If vodou is a

religion of remembering the past, and the Bois-Caēman is a ceremony that

reminds the practitioners of their collective struggle for sociopolitical

independence, then the zombie is a reminder of the failure of that struggle and

of the continued economic exploitation and racism that exists in Haiti today.