Method and Apparatus for Alerting Birds and other Animals, US

6,250,255

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reducing bird strikes |

|

|

|

|

at the airport |

|

|

with 21st century biotechnology |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Licensing available from

Virginia Commonwealth University

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bird Microwave Hearing

Dizzy beam removes birds

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Problem

planes: quieter, faster

birds: face into wind

most strikes on landings and takeoffs |

|

- Aviation Safety

- USAF 1 death / 2 years

- 24 died Elmendorf AFB

- Aviation Cost

- USAF > $50 Million / year

- Airlines > $30 Million / year

|

|

|

|

Solution

microwaves: sound at the speed of light

induce attention and dizziness |

|

Microwave ear and brain responses

birds hear and get dizzy with microwaves

|

|

|

|

|

Bird sensitivity can be obtained using brainstem evoked potential

technology much like hearing screening in modern hospitals for

infants. This is the equivalent of a bird microwave audiogram.

Dizziness is induced by using very low pulse rates or using the

microwave heating effect. |

Microwave Thresholds

much like mammals

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Low Power needed for ear effect |

|

Ultrasonic Interaction

producing as new tone at the bird

Principle: two different ultrasonic frequencies will interact

at their intercept (bird) and will produce their frequency sum

and difference. The difference frequency is used to alert the

bird. The difference frequency is also in the beam, and can "follow"

a bird much like a spot light. The ultrasonic beam can be a tone

or amplitude modulated to carry complex sounds such as bird cries.

|

|

|

|

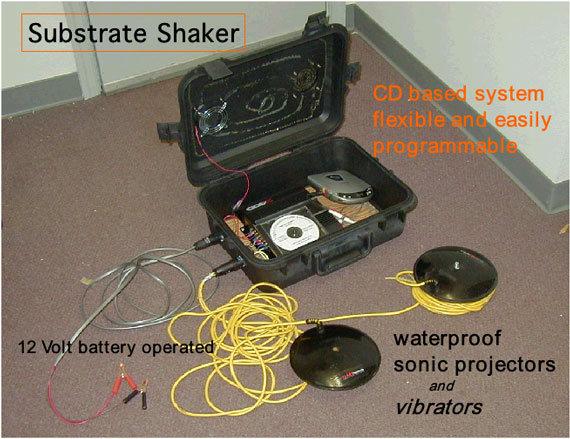

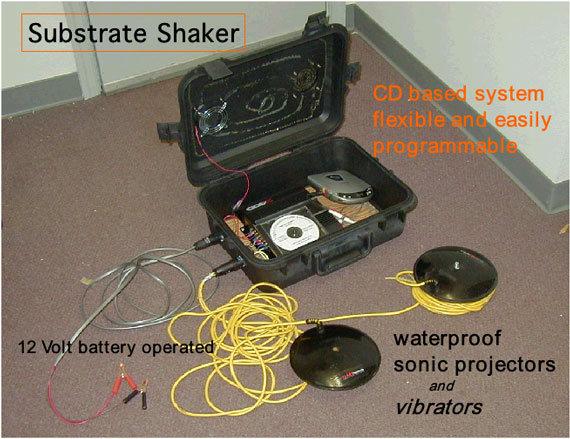

Substrate Shaker

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Very low frequencies for stimulating the bird's body

- Found to be very effective with primitive birds such as waterfowl and pigeons*

|

- Hawk calls can be interweaved with vibration to produce distress

- Crows and passerine distress cries can also be added

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A Virginia Commonwealth University Biotechnology

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Virginia Commonwealth University |

|

|

|

|

|

Aviation Safety

Revised: September 2001

Bird Infrasound (a.k.a. Birdstrike Prevention/Survival)

Bird Infrasound is an SBIR effort that completed Phase I in FY 94 and began Phase II at the end of FY95. Results from the Phase I effort show that birds detect and respond to infrasound, that modulated radar/modulated microwave radiation can be "heard" by people and animals, at higher energy levels birds avoid radar, and it is probable (but not yet proven) that birds will also be able to "hear" modulated radar. Since bird hearing and balance functions are anatomically close together, it might be possible to also have a modulated radar signal that would cause temporary dizziness in birds but have no effect on people or animals. This information will be a key part of future bird control efforts. The use of infrasound signals to alert birds to an aircraft approach and thereby improving their ability to avoid the aircraft is a low cost, low risk, high payoff effort. The Phase II effort will study the effects of infrasound and modulated radar on bird behavior. Infrasound emitted by aircraft, infrasound generators adjacent to runways, and modulated airborne and ground-based radar are all potential ways to reduce aircraft birdstrikes. Modulating radar with an infrasound signal, bird distress calls, and/or a dizziness inducing signal may each be effective in causing birds to avoid aircraft, glide slopes, and runways. A prototype system will be developed, tested, and evaluated in its effectiveness at using infrasound and/or modulated radar in keeping birds away from aircraft. This program will investigate the use of this system by both military and commercial aircraft and airports. The ultimate result from this program is a potential $1B/year savings to worldwide aviation.

Oct 07, 2001

Microwaving birds can be dizzying safety measure

MCGREGOR MCCANCE

TECH NOTES

One of Gene McDonough's Lear jets had just taken off from Washington

when it struck a goose.

The bird hit a leading edge of the jet wing, near its fuselage.

McDonough's pilots were forced to land at the next available airstrip.

The repair bill ran $20,000.

"Almost every pilot has hit a bird," said McDonough, president

of Million Air-Richmond. Based at Richmond International Airport,

the company services, fuels and stores planes.

"Usually, it's just a bloody mark, but those are the small birds.

Big birds can do serious damage," he said. "They can shut a jet

engine down and go through a windshield."

Bird-strike worries are nothing new. Military and commercial airports

have tried different techniques to keep gulls, geese and other

species out of flight paths.

McDonough last week flew to a Quebec City airport. Units lining

the runway there contain propane canisters, which "fire" intermittently

to scare off birds.

But birds acclimate quickly. Yesterday's frightening noise becomes

today's background noise. Ask anyone who has tried gunshots or

fireworks to displace a roost of stubborn buzzards.

After nearly a decade of research and experimentation, a Medical

College of Virginia biomedical engineering professor thinks he

has a permanent solution.

Make the birds dizzy.

Martin L. Lenhardt won a patent in June on the "microwave dizzy

beam" and two accompanying technologies developed to reduce the

number of bird strikes.

He's now searching for an airline or even an insurer that would

test the technology at an airport, help get safety approvals and

eventually make it a commercial product.

"Birds don't like to be dizzy," Lenhardt said. "This is, I think,

our niche to make it effective technology."

The Air Force and a variety of other sources have pitched in a

total of about $1 million in grants since 1993 to advance the

research. Sounds like a lot. But it's not so much, Lenhardt says,

in comparison to the estimated $500 million in annual damage to

U.S. civilian and military aircraft because of bird strikes.

A group formed to raise awareness of the problem, Bird Strike

Committee USA, says more than 400 deaths in the United States

can be linked to strikes.

"This is a worldwide problem," he said. "These things are basically

small bullets. They'll go right through the fuselage of a plane.

The force of a goose hitting an airplane is the same as you driving

into an elephant."

Lenhardt and co-inventor Alfred Ochs of Richmond discovered that

birds react differently to microwave-generated pulses.

Certain frequencies are ignored. But at about 1 gigahertz, a frequency

just above that used by cell phones, audible pulses confuse a

perched bird, which quickly tries to get out of the field. A bird

in flight will twist into circles and also try to flee the irritant.

"Birds are terribly resilient. You've got to avoid the habituation,"

Lenhardt said. "That's the key."

So far the birds have shown no stomach for getting used to microwave

pulses or Lenhardt's other two techniques - the "ultrasonic alerting

beam" and the "shaker startle."

(None of these, Lenhardt says, harm the birds. Unlike an early

technology another scientist had, which relied on a more powerful

microwave beam. The birds basically fell from the sky when they

encountered the beam. Their brains had been cooked.)

The alerting beam works with the dizzy beam. Lenhardt said birds

hear a popping noise, making them alert. That makes the dizzy

beam more effective.

The substrate shaker produces vibrations that birds such as pigeons

and waterfowl find annoying in water or hard surfaces. The device

also can mix in hawk calls, another distressing sound for many

birds.

Important details must be worked out before Lenhardt's technology

is ready for the market.

He, and whomever might sponsor further testing, must prove the

device won't interfere with other communications devices. The

final form of the beam transmitter, whether on the ground near

a runway or in the nose of a jet, is undecided.

Lenhardt figures he must craft a marketing strategy that offers

all three technologies as one package, instead of individual products.

"Airports want something," he said. "It's a matter of getting

this together in a reasonable package."

Gene McDonough, for one, wishes Lenhardt the best of luck.

Contact McGregor McCance at (804) 649-63480 or mmccance@timesdispatch.com

This story can be found at : http://www.timesdispatch.com/business/MGB8541ZHSC.html