The

Evolution of Colour in American Comic Books by Robert

Lupton

|

For many young Americans, the colourful

world of the superhero comic provides relief from the grey

world of school, homework, and chores. However, the world

into which the youngsters escape has changed from generation

to generation. In the original DC comics of the 1930's and

1940's, colour tended to be eye-catching and unrealistic;

just look at Superman's vibrant red, blue, and yellow costume

(though there were exceptions, such as the shadowy Batman

or the grey world of horror comics). As comics began to

take on a more adult audience in the 1970's and 80's, and

better printing processes were simultaneously being developed,

comic book colouring became more artful. Rather than having

brightly-costumed superheroes perform their elaborate dances

on flat planes of colour (sometimes simple backgrounds were

sketched in, but they were almost always coloured with one

flat shade, usually a blue-grey that wouldn't take any attention

away from the action), a new generation of colourists became

acutely conscious of colouring as a device that could establish

mood, character, depth, and dimension.

|

|

From Avengers #34,

November 1966

|

By the middle of the 1960's, the colour

of American comics was virtually indistinguishable from

thirty years earlier. Though advances were being made in

the printing industry, the comic book industry's "turn

'em out" philosophy prevented any real artistic strides

from occurring. Single artists, writers, and colourists

worked on half a dozen or more books per month, the sheer

volume of work they were called upon to produce preventing

them from concentrating too long on any one aspect of the

process.

Perhaps due to the time constraints on

writers, colour choices were made on the fly, and if they

had any narrative import, it was cursory at best. In the

example at left, one can see this in action. In a panel

like this, individual colours are so intense that they cancel

each other out; the artist obviously hasn't put enough thought

into the work to realize that a more deliberate use of colour

would have been more successful. For instance, the red beams

of light that result from the impact of the super-villain's

laser blast hitting Captain America's shield would have

been more intense on a field of black, as a black background

makes red seem more saturated. If the artist's intention

was to create a colour scheme that emphasized the chaos

of battle, his choices were brilliant; however, if he was

attempting to focus the viewer's eye on the locus of action,

i.e. the laser hitting the shield, he could have been more

successful.

One can also find some degree of significance

in the characters' costumes. Captain America, created during

World War Two, wears the colours of the country that he

protects, but Hawkeye's bright purple fatigues would do

little to camouflage him from a potential assailant (at

least in a world with a palette as earthy as ours). In general,

the heroes of the stories were clothed in bright, vibrant

colours (Spider-Man, Superman, The Flash, etc.) while the

villains tended to be rendered in earthy browns and greens

and metallic greys (Doctor Octopus, Fing Fang Foom, et al).

This dichotomy set up the battles in comics as not only

good versus evil, but the world of excitement and colour

resisting mundacity and boredom. However, these were only

general patterns and rules of thumb, subject to the whims

of creators and editors.

|

|

One other issue that must be noted when

discussing comics before 1980 is censorship. After the publication

of Dr. Fredric Wertham's Seduction of the Innocent (a

book that linked violent comic books with juvenile delinquency),

the comic book industry was forced to police itself, eliminating

violent and mature content from its books. The Comics Code

Authority was a group created to perform this function,

and adopted a set of typically bizarre rules and regulations

that would presumably foster more desirable qualities in

America's youth. Predictably, most of the standards deal

with the content of the story, but the Comics Code's standards

did have some effect on colouring. The most egregious example

is General Standard A7, "Scenes of excessive violence

shall be prohibited. Scenes of brutal torture, excessive

and unnecessary knife and gun play, physical agony, gory

and gruesome crime shall be eliminated." In practice,

torture, physical agony, knife and gun play, etc. were all

present in comic books, but the Comics Code Authority refused

to place its seal on any comic where blood appeared red,

forcing colourists to find creative ways to convey the fact

that it was blood the penciller was drawing. Similarly,

the stipulation that "Nudity in any form is prohibited"

didn't really eliminate sexually suggestive material in

comics, but forced artists to find their way around the

most explicitly detailed infractions. Though nude women

didn't appear in comics, more often than not female characters

wore skintight spandex costumes whose only real differentiation

from the nude body was its bright colour. At least in regards

to these regulations, the artist who produced the black

and white line drawings had little to change in his technique,

and the responsibility of complying with the code fell to

the colourist, who had to present the artist's work in the

most innocuous context possible.

|

|

By the 1980's, however, the tide was beginning

to change. With the success of independently produced comic

books such as the phenomenal Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles,

many of the old industry rules became antiquated. Since

the new, edgier independent comics were sold almost exclusively

in specialty shops, their publishers had no real reason

to submit their work for approval by the Comics Code Authority.

Secondly, since many of the smaller-budget comics couldn't

be printed in four colours because of cost constraints,

they simply printed the black and white line drawings as

finished work. Before long, black and white comics such

as The Tick and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (both

of which spoofed the superhero genre that was the major

publishers' bread and butter) made a lack of colour an asset,

and more mainstream comics seemed pedestrian in comparison.

Finally, with a significant market share, independent publishers

could now lure top creators from the two major publishers,

Marvel and DC, making artistic freedom a viable issue. Though

smaller publishers still couldn't offer very much money,

they could offer a smaller workload, ownership of

any characters the artist created, and total artistic license.

On the other hand, with toy lines, movies, and cartoons

constantly in production for the major companies, the comic

book version of any given character couldn't differ significantly

from the version in any other media, effectively restricting

creators from anything other than subtle changes in their

characters' appearance or personae.

|

New England Comics' The

Tick, one of the most successful independents.

|

| Of course the major publishers

weren't about to begin publishing their books in black and

white, so some small advancements in the technical side of

the colouring world were made. The number of dots per inch

that could be printed were increased dramatically, resulting

in a larger palette and subtler gradients. However, before

any really noticeable reforms took place, the post-Reagan

recession took hold in the United States, wiping out virtually

every independent comics publisher. Even the almighty Teenage

Mutant Ninja Turtles couldn't survive the economic downturn,

becoming a nonentity for nearly a decade. |

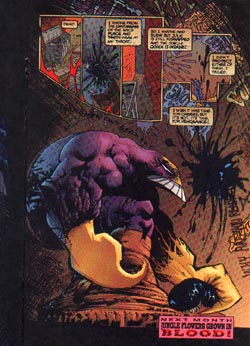

Image Comics' The Maxx

|

During

the recession, the major publishers had as many economic

problems as the smaller publishers, and new methods had

to be found to promote the books, especially to the specialty

audience that had solidified during the 1980's. One of the

publishers' solutions (Marvel Comics in particular) was

to hype not only the characters and stories featured in

the books, but the creators as well. Though virtually no

one paid attention to who created a comic book twenty years

earlier, every comic fan had a favourite writer and artist,

and rather then being a lifelong fan of a character, fans

now dedicated themselves to creators, following them from

book to book. Soon, most creators (artists in particular)

were forced to produce only one book per month, and received

outrageously large salaries for this significant drop in

production. However, the effect was that comic books became

much more artful as creators had more time to devote to

them. Unique panel arrangements, detailed backgrounds, and

progressive plotlines that would have been unheard of years

ago were now commonplace. The only problem was that creators

enjoyed this artistic freedom so much that they began to

feel constrained even by the newly undemanding editorial

staffs at the large publishers.

In

1991 seven of Marvel's top creators left to start their

own company, Image Comics. Though the split with Marvel

was ostensibly due to the fact that the artists had to relinquish

ownership of the characters they created, there were countless

changes in this new line of comic that would revolutionize

the industry.

|

|

First of all, the new Image comics lacked

the Comics Code Authority's seal of approval. While some creators

dealt with adult topics that would not have pleased the Comics

Code, and some just wanted some good old fashioned gore, no

one particularly wanted to have their newly unhindered artistic

vision censored by some antiquated, irrelevant organization.

Secondly, in a decision that would forever revolutionize the

way that American comic books are coloured, Image comics decided

to hire an outside studio to computer colour all of their

comics. Also, rather than merely printing the cover on high-quality

paper, Image collectively decided that the entire comic should

look as great as the cover. Whereas computer coloring wouldn't

have done much for the pulpy newspaper stock that Marvel and

DC were still using for their inside pages, every drawing

in an Image comic could be viewed as a work of art in and

of itself.

Note the example from Image Comics' The

Maxx above. This mature sense of colour would have been

out of place in virtually any comic of an earlier time period.

Rather than simply using a single light source that lights

the figure, the main panel features a harsh light source that

is focused just to the right of the figure, and the blueish

tint of The Maxx's back betrays a subtle second light source

behind the figure. Both this subtle lighting scheme and the

printing process that allowed it to be illustrated so effectively

were nothing short of revolutionary, and lend an air of realism

even to penciled artwork as overtly stylized as that found

in The Maxx.

The large publishers raced to catch up with

Image, who were quickly eating into the large market share

that Marvel and DC had enjoyed during the recession. However,

as virtually every comic switched to computer colouring at

nearly the same time, there weren't enough colourists to meet

the demands, and there was a great deal of on-the-job training.

Gary Scott Beaty notes that "coloring was getting out

of hand. Every bump was formed with a grad, every belt buckle

had a lens flare and every strand of hair was 3D. In my opinion,

it took a while for the initial excitement of what COULD be

done gave way to a real assessment of what SHOULD be done.

I admire the painterly approach, as long as the basics of

painting are applied. Much of that early 1990s stuff ignored

(A) where the light was coming from, (B) shaping the figure

instead of hiding it and (C) separating foreground from background."

Another reason for the wildly inconsistent nature of comic

book colouring of the period was the lack of editorial control;

both Image and the major publishers outsourced their computer

colouring to studios like Steve Oliff's Olyoptics, who did

their own quality control work. An editor's only real solution

to a poor colouring job was to have the book redone, which

is almost completely unfeasible for the comic book industry's

rigorous publishing schedule.

In today's booming comic book industry, all

of the trends in colouring have pretty much leveled out. Virtually

all large print-run books are now computer coloured, but the

"kid with a new toy" aesthetic is now pretty much

gone. Comics are now coloured artfully, and with a conservative

sense of style rather than blatant flair. Black and white

comics are still largely out of the mainstream, but a few

artists have demanded that their high-profile projects be

published without colour, restoring the air of respectability

to one-colour fare. Also, the Comics Code Authority is quickly

losing any last shreds of influence, as the number of comics

sold on newsstands rather than specialty shops dwindles ever-toward

the zero mark. The progression of comic book colouring is

likely not over, though. Constant strides in the domain of

computer software and process printing will allow colourists

more and more freedom, and even if we have seen the last "revolution"

of comic book colour (and likely we haven't), like any other

art form the medium will continue to evolve. As pop art, comic

books, and their colour in particular, will always be a gauge

of the American social consciousness and aesthetic, and beyond

their interest as a lively art form, they will always be important

because they are the world into which we choose to escape.

Selected Bibliography:

http://www.comicartistsdirect.com/coloring.html

- A concise history of colour in American superhero comics,

if a bit on the technical side.

http://www.dccomics.com/ - DC comics has been

around for more than 60 years, and the the images on their

web site will explain to these concepts to the newcomer in

terms we all recognize: Superman, Batman, the Flash et al.

http://www.cbldf.org/history.shtml - A short

history of censorship in comics penned by the folks who wish

to abolish it, the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund.

http://www.geocities.com/Athens/8580/cca.html

- The original standards used by the Comics Code Authority

to evaluate comics. An interesting piece of history, but disturbing

when one realizes these standards are still being enforced

today.

|

|