George Cruikshank: A Focus on His Book Illustrating Career by Shakti Mehrotra

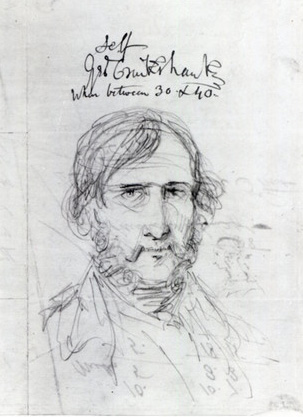

| When many think of George Cruikshank, they think of the acclaimed English graphic illustrator and caricaturist of the nineteenth century. He followed in the footsteps of the great satirical graphic artists before him, William Hogarth and James Gillray. Cruikshank's distinctive works on paper primarily focused on English politics as he ridiculed the Whigs and Tories of his time. In later years, he exhibited his talents in creating book illustrations as well as championing social causes. Through his intense energy and fertile imagination, Cruikshank produced about five thousand works during his lifetime. | Though a good part of the artist's life focused on caricatures and such similar arts, henceforth, a greater focus will be placed on his ability and skill as a book illustrator. Cruikshank began his venture into book illustration in 1819 - 1821 with the publication of The Humorist. In fact, the majority of the work that he produced from about 1830 to 1845 was book illustration. During this period, many of the novels that he illustrated were published in serial form. He produced extensive work for Bentley's Miscellany and later Ainsworth's Magazine. | Cruikshank's relationship with his peers from Bentley's Miscellany became unpleasant and he began to produce poor work for the serial just so he could break from it. It has been thought by many that Cruikshank plunged into book illustration to truly unleash his talent for humor and to address social ills in his own personal and unique style of commentary. However, it must be stated that Cruikshank's eccentric personality is legendary and made it very difficult for him to work congenially with almost anyone. |

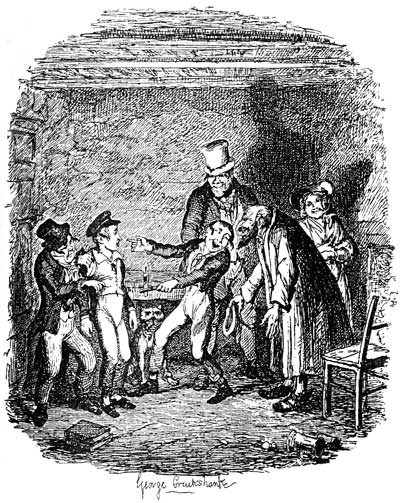

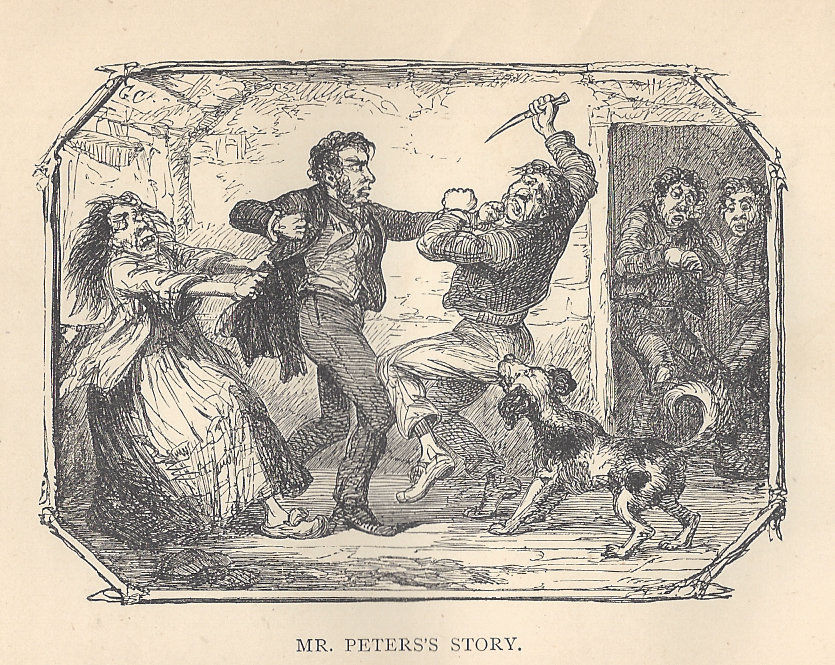

| The publication that brought his talents to the forefront for public view was Points of Humor, which was issued in two parts between 1823 and 1824. In addition, Cruikshank's illustrations found their way into many children's stories, such as Cinderella, Robinson Crusoe, Punch and Judy, and others. Cruikshank also did work for other types of popular novels such as Tom Jones. Perhaps Cruikshank's most celebrated and noteworthy collaboration was with Charles Dickens in the publication of the serialized Oliver Twist in 1838. As the popularity of the novel grew, the relationship between artist and author became more and more strained under the pressures of making publication deadlines. Both individuals had strong wills and opinions about how to develop the novel, and there was a constant battle for control of the project, which would determine where the creative emphasis would lie: with the text or with the illustration. In spite of these opposing point of views, Cruikshank completed his work on Oliver Twist, and his illustrations received high praise. Yet, the project left him disillusioned and bitter. The relationship with Dickens was almost typical of most of Cruikshank's creative collaborations throughout his career: he often felt cheated and taken advantage of, never receiving the credit and acknowledgment that he thought he rightfully deserved. Like Hogarth before him, Cruikshank felt an unpleasant dependence on booksellers. He felt that the only way to be free was to publish his work independently. |

|

Some of Cruikshank's self-published works were Phrenological Illustrations, 1827; Scraps and Sketches, 1829; and My Sketch Book, 1834. Cruikshank's publications not only allowed him to enjoy artistic freedom, but they also allowed him to attack those that angered him. For instance, one publisher used his last name without noting that the work was by his brother Robert Cruikshank and not George Cruikshank. Therefore, in one of his later works, "Cruikshank is shown pulling the nose of the offending publisher" (Ted Stanley).

|

|

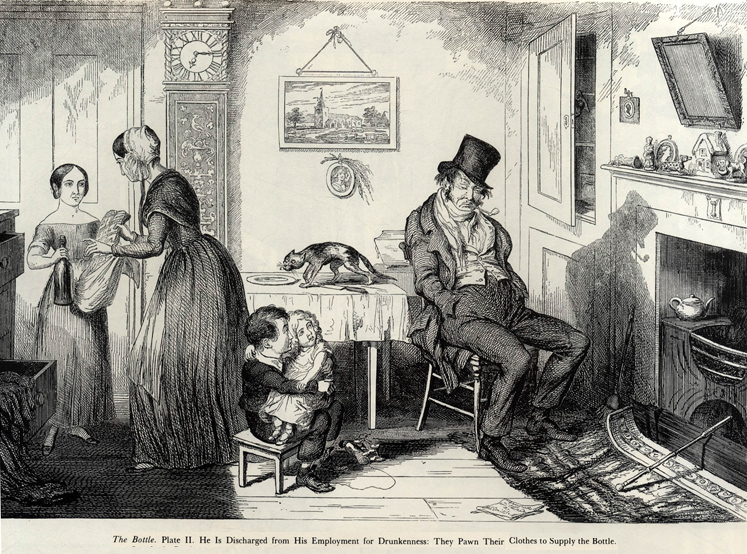

Cruikshank also used his publications to champion social causes and bring to public light what he perceived were acts of negative behavior, such as drinking alcohol. In his famous publication The Bottle, Cruikshank illustrates the terrible repercussions that drinking can have upon a family. Cruikshank's harsh view on the subject is not surprising. He was one of the most active and vocal proponents of the Temperance Movement in nineteenth-century England. Some of the more chilling and sobering of Cruikshank's illustrations are to be found in Maxwell's History of the Irish Rebellion in 1798. These illustrations, similar to the work of Goya, show the cruelty and inhumanity found in war. |

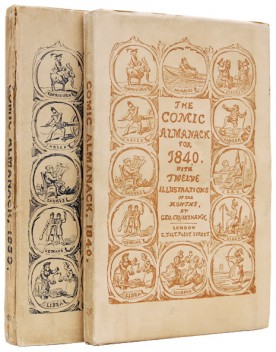

| One of Cruikshank's most successful illustrated books is his series The Comic Almanack, which was published from 1835 to 1852. It contains an etched plate for each month adorned with small decorations and vignettes in woodcut. About 250 etchings were produced during its issue. The plates are depictions of everyday life in London. The images are Cruikshank's own satirical commentary on a wide range of social and environmental issues. |

Home - Student Projects - Next