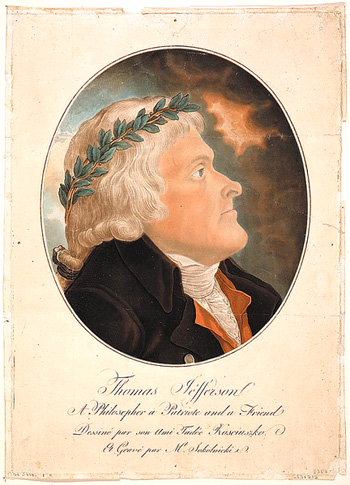

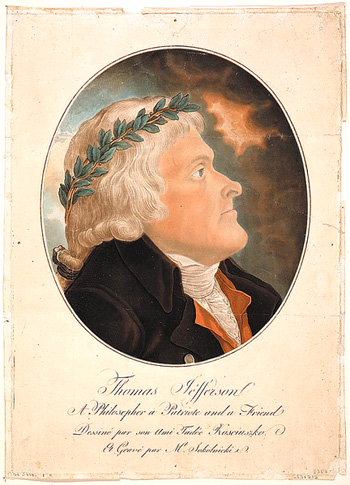

Tadeusz Kościuszko, “Thomas Jefferson,” ca. 1815

Tadeusz Kościuszko, “Thomas Jefferson,” ca. 1815

|

The New American Republic, 1780-1830

Even after the United States won the Revolution, this victory did not immediately guarantee national unity or a clear sense of what it meant to be “American.” The period that came to be known as the “early republic” was marked by intense struggles—for political stability, in acquiring new territories and conquering wildernesses, in developing new industries and economic markets, and in creating a new body of arts and letters. Throughout these struggles, new kinds of social groups fought over participation in the new nation—Southern planters, female intellectuals, small farmers, enslaved peoples, displaced native peoples, Jeffersonian democrats, and Hamiltonian federalists, to name a few. In short, the Revolution didn’t so much constitute a satisfying ending to conflict, but a very messy beginning for new forms of it.

This class will examine the competing voices and debates in this crucial era by focusing on the shared concern to create a new nation and a new culture. We will particularly focus on the larger question, “What did the Revolution mean?” as it pertains to the situation of different individuals over time—first within the specific realm of politics and establishing a federal Constitution, and second in a broader range of settings, including religion, work, domestic life, sexual relations, and historical memory. You will continue to plumb this question with your research papers. Overall, we will see that despite their impulses to find a common ground of identity and culture, the United States was a multivalent, complex society by 1830—one that still worried about the possibility of falling apart, perhaps even by a civil war.

|

Tadeusz Kościuszko, “Thomas Jefferson,” ca. 1815

Tadeusz Kościuszko, “Thomas Jefferson,” ca. 1815