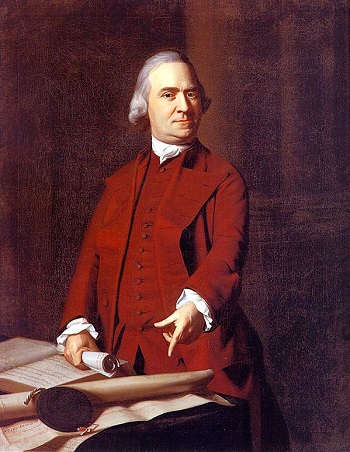

John Singleton Copley, Portrait of Samuel Adams, ca. 1772 |

The American Revolutionary Era, 1760-1820 The greatest misconception about the Revolution may be that it was an uncontroversial choice for Americans to rebel against Great Britain--and that the end of the war brought a smooth transition to liberty and democracy. This class examines the many conflicts before and during the war, as American colonials debated whether declaring independence might be the right choice, and what democracy might look like in a regionally isolated country. In addition, this class examines the postwar conversation among African Americans, women, Indians, members of ecstatic religious sects, and poor men who each contributed new ideas to the nation. When the war concluded, members of each of these groups found reason to believe that liberty might mean something more than political independence from Britain, and that they might claim civil rights using the powerful revolutionary language of democracy and freedom raised during the war. Moreover, many countries beyond the new United States likewise felt inspired by American revolutionary ideals, including France, Haiti, and many Latin American countries. This class asks, why did some Americans refuse to support the rebellion? What did freedom mean to those who had neither money nor social rank? How revolutionary was the Revolution, and how radical were its outcomes? What did Americans think about subsequent revolutions when those wars were undertaken by slaves or Mexicans, or when the French started beheading members of the aristocracy? And finally, why are we still fighting about the Revolution and its legacies--"freedom," the divide between church and state, the meaning of the right to bear arms, and whether in a democracy ordinary soldiers matter as much as political or military leaders? |